16 tons and what do you get? Salmon smolt if you’re lucky!

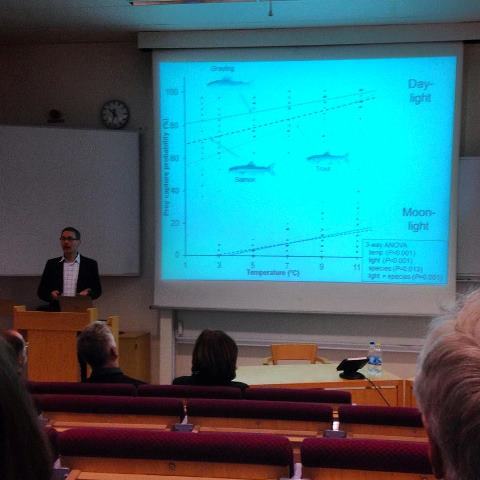

Posted by Daniel Nyqvist | Projekt KlarälvenJohn Piccolo, researcher at Karlstad University has written a short story for the Freshwater Working Group of the Society of Conservation Biology about his work in Klarälven. Read the story at the group’s facebook page or here below:

“This is a story about some of the toughest field work I’ve carried out in over 20 years of research on salmon populations in either North America or Sweden, and describes the first documentation of a wild Atlantic salmon smolt run on the River Klarälven in central Sweden.

Klarälven is the longest river in Scandinavia, and is home to one of the world’s last remaining large-bodied landlocked Atlantic salmon (pictured) populations. The landlocked salmon migrate from Vänern, the largest lake in the EU, to spawn and rear in Klarälven (learn more about Klarälven here). After living for 2-4 years in the river, the salmon smolt migrate downstream to feed and grow in the lake. Although there has been anecdotal information about the smolt migration for many years, nobody had ever succeeded in trapping them to estimate production. Due to historical fishing pressure, and hydropower development, the Klarälven salmon are believed to be highly-threatened. However, salmon populations could also be recovering in Klarälven, because fishing pressures have reduced, and populations have gone from a low of less than 100 spawning adults to a record return of over 1000 in 2016. With this history in mind, we set out to better our understanding of salmon smolt populations in Klarälven and to guide more successful management and restoration.

As many aquatic scientists know, trapping fishes or even invertebrates in rivers can be difficult – they all tend to migrate during rising or falling flows when water levels in the river are high. Keeping a net in the water can be difficult or impossible under such conditions. Months of organic debris that has been deposited along the river banks is suddenly washed into the stream, and nets need to be cleaned often, sometimes hourly 24-hours round. An additional variable in the mix is that in large rivers, organic debris can be large (picture large tree branches or even entire trees!)! High water levels, rapid flows, and large debris are challenging obstacles, and if these obstacles bring our sampling gear down, it can be quite dangerous to get the gear up and running again. I did my first smolt trapping back in 1996 on the Salmon River in Idaho, USA. I remember watching a mature conifer tree some 30 meters long being sucked into an eddy like a drinking straw, and being ejected clear out of the river on its’ way downstream. The power of a flooding river is truly awe-inspiring.

It took us four sampling seasons, filled with trial and error, to achieve partial sampling success for our project. The first year we tried floating smolt traps like those often used for Pacific salmon. Although these can be adequate when there are large numbers of smolt migrating, we did not catch sufficient numbers of smolt to make mark-recapture estimates. During years two and three, we imported stationary traps, a Finnish design, that are anchored to the river bottom with 3-4-meter-long thick iron poles. It takes two days of hard labor for a work crew to drive these into the substrate by hand, balancing on the deck while holding the boat in position in the strong river flow (see photos). Inspired by the work to setup these Finnish traps, the title for this story comes from the classic song about mine workers – the iron bars didn’t weigh 16 tons, but just setting up the net was A LOT of work. Once the net was installed, the hard work began. Cleaning and emptying the net every day, and waiting for the spring flood to bring the salmon smolt. Although I was involved in this work, it is really our field crew that deserves most of the credit – it was a 24-hour a day, 7-day a week job, cleaning every day and staying vigilant for possible emergencies. During years two and three we came close to success – we had begun to catch larger numbers of smolt just at the time when flows became unmanageable and the net had to be removed. These years involved a lot of trial and error in operating and maintaining the net, cleaning, sewing mesh, clearing debris. The worst of it was cutting the net out during high flows, just when it seemed the smolt were beginning to run.

Each year we’d improved our technique and catch; the second year we caught over 300 smolt, and made our first rough estimates of production. However, we had yet to document a substantial wild smolt run. We managed to scrape together enough funding for one more try, and set to work for our final attempt. With two years’ experience, we installed the net in record time and had a good cleaning and maintenance routine. The field crew was on the job every day and smolt numbers began to climb as did the prognosis for the spring flood. They managed to continue to fish the net right into the beginning of the flood, and finally, on the last five days that they could fish before the flood, they hit the jackpot! SMOLTS! The field crew caught over 1000 smolt during their last five days – 425 the day before they had to remove the net. This one-week catch exceeded the total number of smolt we’d caught the previous two years combined. Our mark-recapture estimates suggest that over 15,000 wild salmon smolt migrated that year, documenting substantial production of wild landlocked Atlantic salmon, probably the largest remaining population in the world. Our hard work and persistence paid off – national and international awareness of the Klarälven salmon has continued to grow, and they are the focus of renewed efforts to maintain and restore wild salmon populations that have been impacted by centuries of anthropogenic impacts.”